Great article! I think we are united in our desire to revive useful aspects of memetics, as well as to synthesise cultural evolutionary theories with the study of Internet memes. A great paragraph summarising this position, from your article (pp. 8-9):

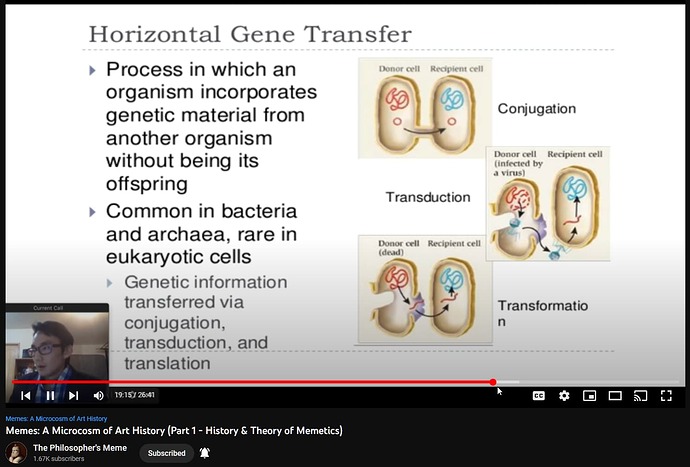

Many have criticized memetics as a failed analogy to genes as replicators but what if we make the analogy on different biological grounds? Biological theory is not homogenous and unified and organism-derived adaptations to the environment (such as in niche construction cases) have been left out of the received view in biology. But what if we take them seriously and liken memes to the environmental modifications that organisms make instead? What if memes are treated as constructed artifacts that have a propensity for rapid propagation between populations? Maybe then we could escape the problems of a selfish view of memes where human individuals are treated as possessed zombies existing as servants to the self-replication of their memes. But this will require narrowing down the scope of memetics to something less ambitious than a general theory of cultural evolution. So, instead of seeing memetics as a competing paradigm for cultural evolution we can rather treat it as a complementary paradigm to theories of social learning, niche construction and shared attention. If the ontological baggage of the meme-gene analogy is left behind we can mix these together, creating a more integral account of cultural evolution where memetics is just part of the solution but not the whole solution. GCCE provides an account of selection criteria and replication success (that memetics was lacking as we saw in Section 2.), as well as an empirical paradigm that can study cultural evolution through behavior. Joint attention provides a cognitive mechanism for how imitation and thus replication from one individual to another happens in a social context (and can compliment mirror neuron accounts) and niche construction provides the theoretical and empirical background for rejecting the selfish meme analogy and a ground for the position that memes don’t just float around in a hypothesized semantic space but are constructed by agents to satisfy certain functions. All of the above are externalist approaches because they do not need to hypothesize mental representations and neural mechanisms behind the replication processes in order to study them empirically. Memetics can itself be part of that picture too if we consider the dynamics of propagation as its most important feature. The rest can account for the origins of cultural traits and cumulative cultural evolution but have difficulty in dealing with cases of rapid propagation and the spread of informational entities like beliefs and ideas, whereas memetics can easily account for them.

I have to emphasise here that criticisms focusing on the "viruses of the mind" rhetoric from Dawkins is precisely incoherent in their characterisation of Dawkins as a strong determinist: in The Selfish Gene, Ch. 11, "Memes: The New Replicators", Dawkins ends by saying that humans aren't automatons controlled by memes (or genes, for that matter), and that we should "rebel against the tyranny of the selfish replicators" to further enhance our autonomy. Memetics isn't intrinsically deterministic about free will, and never has been.

I think that addressing this pretheoretical concern about the definition of memes (and culture, and personhood, and meaning, etc. for that matter) will be absolutely crucial to a programme that aims to integrate cultural evolutionary theories with cybercultural research. Even when some disciplines have addressed such issues in their own way and have moved on, researchers frequently lag behind in updating their knowledge about other disciplines (of course, this is not at all limited to meme studies or any one field). It would be essential philosophical work to cover this in a way that doesn't confine itself to an "evolutionary biologist" language.

That being said, I can't help but find it highly appropriate to contemporary cyberculture when I read Keith Henson's 1985 article about memes (sometimes) taking over minds (2003):

In inducing their own replication, memes are conceptually related to genes that influence the bodies in which they reside, directly or indirectly, to replicate the genes. "Your" genes, incidentally, are not the only ones that influence your behavior. Consider the fact that a lowly cold virus turns you into an atomizer for propagating itself by activating the sneeze reflex. An even more impressive example of one organism's behavior being influenced by another's genes is the case of an ant brainworm that cycles between ants and sheep. It causes the ants it infects to climb up a grass stem and wait there for a sheep to eat them.

Sometimes "your" memes can have this much influence. We need a name for victims that have been taken over by a meme to the extent that their own survival becomes inconsequential. "Memeoids" is my suggestion. You see lots of these people on the evening news from such places as Belfast or Beirut. Less extreme cases haunt the airports with signs about feeding Jane Fonda to the whales.

Saying people get "brainworms" and become "memeoids" sounds exactly like how people talk to each other on Twitter. Powerful stuff.

Your approach to developing a unified and empirical theory of memes is powerful because it implies a modular design of the theory. I wonder if we could combinatorially develop alternative theoretical frameworks using this modular way of thinking. If we determine that a theory of memes must answer such and such questions, and then provide some way to collate research and theories that each answer one question or another, and finally filter these combinations by whether they contradict one another or not... that would allow researchers to collaborate even across otherwise insurmountable disciplinary boundaries, since most of the research could be done independently first, for instance.

I think that Richerson and Boyd are quite right in their appraisal of memes as a "better mousetrap" (2000):

We do not understand in detail how culture is stored and transmitted, so we do not know whether memes are replicators or not. If the application of Darwinian thinking to understanding cultural change depended on the existence of replicators, we would be in trouble. Fortunately, memes need not be close analogs to genes. They must be gene-like to the extent that they are somehow capable of carrying the cultural information necessary to give rise to the cumulative evolution of complex cultural patterns that differentiate human groups. They exhibit the essential Darwinian properties of fidelity, fecundity, and longevity, but, as the example of phonemes shows, this can be accomplished by a most ungene like, replicatorless process of error prone phenotypic imitation. All that is really required is that culture constitutes a system maintaining heritable variation.

[...]

Memes are not a universal acid, but they are a better mouse trap. Population modeling of culture offers social science useful conceptual tools, and handy mathematical machinery that will help solve important, longstanding problems. It is not a substitute for rational actor models, or careful historical analysis. But it can be an invaluable complement to these forms of analysis that will enrich the social sciences.

Looking back, it kind of feels like classical memeticists were "too early" to a fundamentally correct idea, and that ideas that didn't work back then might just work now, under drastically different circumstances. I think the timing is right for a reassessment.